The precise difference between story and plot changes depending on your source. A friend of mine once said that story contains all the meaning—theme, character, the DNA of a work’s soul. Plot, he claimed, is just the roadmap.

I didn’t argue. I like maps.

I’m a plothead. The idea that one bad decision could destroy a plan has always appealed to me. Fate is a constant character in life, so it’s natural that it appears in fiction. Murder mysteries depend on characters plotting out their murders (or their escape from crimes of passion) and reacting in real time as everything unravels. This is why we need detectives to explain why and how things were done at the end — preferably with suspects gathered round.

When writing my most recent book, I decided to pay a little more attention to story. What happened? The themes became more apparent and the characters became a bit more integral.

First, the theme: I’ve almost always found the theme after a few drafts. That sounds awful, but that’s the way it is. Importance lay in the experience of the mystery. The experience is certainly why I enjoy reading them. Theme was a mysterious element that took me by surprise (and delighted me) when it suddenly revealed itself. Carr has themes the pop up again and again, but I cannot say that I’ve ever read one of his books and admired the meaning. Theme was never my compass—it was a fog bank I sailed into by accident, sometimes illuminated at the last moment.

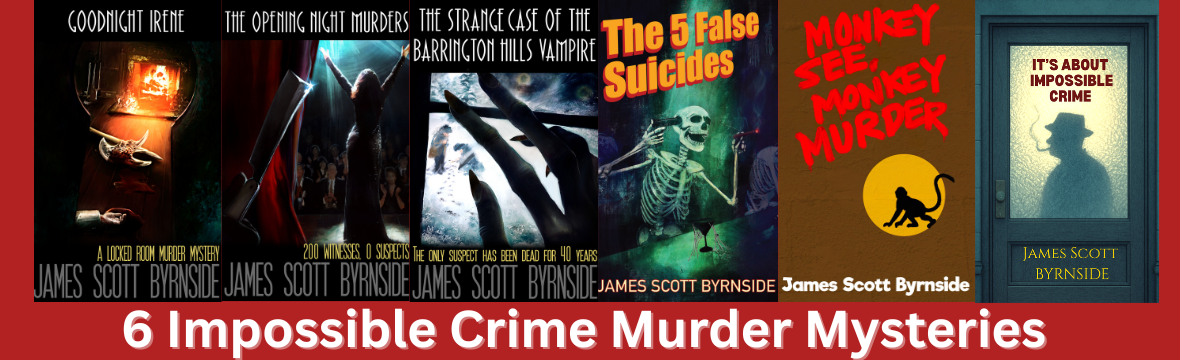

This time (and I’m speaking about It’s About Impossible Crime specifically) I developed a theme and consciously thought about it as I plotted. Erasure is my most common theme, and not only the erasure of life. Tenuous identity and the futility of leaving a mark on an uncaring world are of utmost importance to me.

Character has never been my strong suit. In a world that demands identification, I remain perpetually behind the 8-ball; however, developing theme has brought me a bit closer to using character to move some of the story.

It’s often said that American cinema is plot-driven while European cinema leans into atmosphere and character. That’s no hard rule, but it tracks. A classic European film can entertain you for 2 hours, but leave you speechless when someone asks what it was about. “Well, it’s about this woman and…” When character-driven pieces are bad, it’s because you’ve spent time with people you don’t care about. The experience is boring and pretentious.

Bad American films are not usually pretentious, but rather insultingly stupid. In order for the plot to function, every character has to behave like an idiot at all times. Rational people would never do any of the things those characters do, and the audience is insulted.

Which brings us back to the murder mystery. Focusing on plot will often cause a writer to allow a bit of idiocy into their character. I took more time to reduce idiocy. Perhaps, it was because I paid more attention to story.

And yet…

After a few weeks of thought, I’ve changed my mind. Story and plot don’t exist simultaneously. My friend disagrees strongly, but it’s clearer now.

Story is the raw footage—indigestible, unruly. A slab of marble.

Plot is the sculptor. Plot makes meaning entertaining. It doesn’t have to apologize for that. A great story with a bad plot dies unread. A great plot can give a weak story a pulse. Naturally, you want both. And I’m spending more time with the raw materials.

But plot is still king. Plot is for writers.

Anyway…sales of the new book are doing well. If you haven’t picked up a copy, you are sorely missing out. Take care and I’ll talk to you soon.