The brain can find any way to question the life choices of its vessel. You could be happily skipping down the street without a care in the world and your brain might suddenly shout, “Hey! What if you’re a low-life piece of garbage? Have you considered that possibility?”

Things like that often creep into my thoughts. What if they’re all right? What if you’ve thrown away all your best opportunities? What if you’e going to die in the most claustrophobically-horrifying caving accident of all time?

Yesterday, I had such a crisis of confidence. I read George Langelaan’s short story “The Fly” and then followed up by reading a little about it. “The Fly” is the timeless tale of a mad scientist who invents a disintegrator-reintegrator machine. When he uses himself as a guinnea pig, something goes horribly wrong. A fly enters the machine with him. He ends up with a fly head and arm. Even more disturbing, the poor insect has to live with a terrible haircut. The story is best known now for inspiring the Kurt Neumann B-movie and David Cronenberg’s body-horror masterpiece. But buried in Wikipedia is a passage from Marie-Louise von Franz, Jung’s longtime collaborator,

Here is the passage:

“There one sees how inferior intuition takes shape in a sensation production. Since the story is written by a sensation type, it gets disguised as completely practical sensation. The fly would represent inferior intuition, which gets mixed up with the conscious personality. A fly is a devilish insect. In general, flies represent involuntary fantasies and thoughts that annoy one and buzz around in one’s head and that one cannot chase away. Here, this scientist gets caught and victimized by an idea that involves murder and madness. … At the end of the story the commissioner of police talks to the author and says that the woman was, after all, just mad. One sees that he would represent collective common sense – the verdict finally adopted by the writer, who admits that all this is just madness. If the writer had established the continuity of his inferior function, and had freed it from his extroverted sensation, then a really pure and clean story would have come out. In genuine fantasies, such as those of Edgar Allan Poe and the poet Gustav Meyrinck, intuition is established in its own right. These fantasies are highly symbolic and can be interpreted in a symbolic way. But a sensation type always wants to concretize his intuitions in some way.”

I’m not terribly familiar with psychology, so I had to read this a few times, but I think I’ve got it. The story starts to explore the author’s unconscious, symbolic side (through the fly), but because the author’s main personality type is grounded in literal, physical reality, the story keeps yanking the fantasy back into “this is just madness” territory. As a result, the potential for deep symbolic meaning is lost.

I rejected this at first, because the story ends with a hint that the tale is not just madness. But then I realized the “hint” aspect was the problem. It’s still handled like a curiosity, almost as a “wink” to the reader rather than as a fully developed symbolic reality. It’s still anchored in concrete, measurable detail rather than letting the intuition spiral into its own symbolic logic.

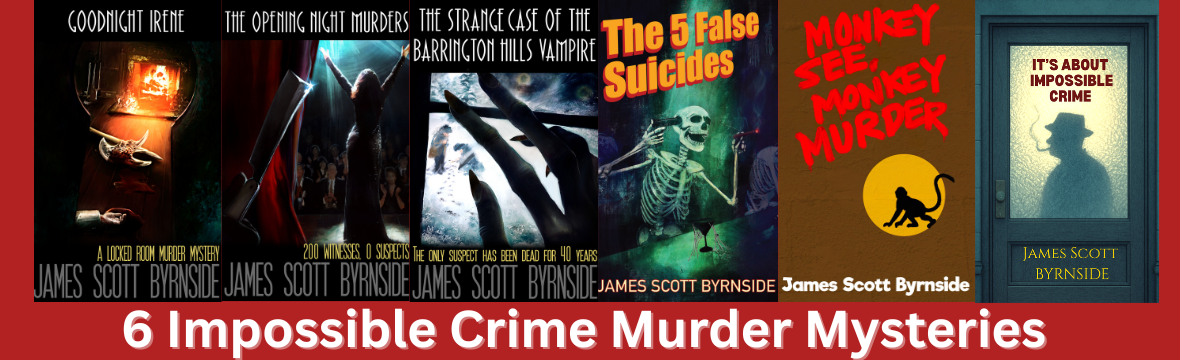

And then it hit me. That’s what I do. That’s what impossible crime fiction is. The strange, in its natural state, wants to be symbolic, intuitive, alive with meaning — like the fly in Poe’s world. But in my genre, we always lock it in a glass case and label it “explained” — not need to panic, my dear reader.

I’m wondering if, in writing these kinds of puzzles, I’m taming something that should be wild. If a reader’s first gasp — “That’s impossible!” — is the fly buzzing at the window, am I guilty of swatting it when I should let it live?

It’s troubling.

Last week I turned 49. Maybe that’s why these thoughts are creeping in. I also cut my hand in a kitchen accident — lots of blood — and every time I tried to type, it reopened. I’m back at the desk now, but maybe the downtime gave my mind too much room to buzz.

Or maybe the thought is correct. Maybe the very thing I’ve always loved about my genre — making the impossible perfectly reasonable — is also the thing that kills it.

Or maybe all this Jungian shit doesn’t matter.

There’s a fly in the kitchen right now. Mocking me.